Chapter Four

Previous Chapter | Next Chapter

There are only three math concepts that matter

By the title of this chapter, you may be wondering why I am contradicting my first chapter. My claim is that behaviours are more important than math. In a way I am, but remember finances are a personalized process and in nearly every instance behaviour will win above the math. But there are still math concepts you need to understand that will set your mind in the right place when it comes to debt, investments, and your spending.

These will not require you to learn math or do math except for one small section. The goal of this chapter is to increase your understanding of these concepts.

Compounding interest

Compounding interest is the first topic that we need to discuss. It was once stated, by Albert Einstein, that ‘Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it; he who doesn’t, pays it’. It is really fascinating that one of the most brilliant minds, one known for his contributions to the scientific community, made such a bold statement about compounding interest. Why would this be? I think it is because compounding interest can have such a tremendous and profound impact on our lives if we properly understand it. Compounding interest means as you earn interest, you begin to earn interest on your interest. To explain this numerically:

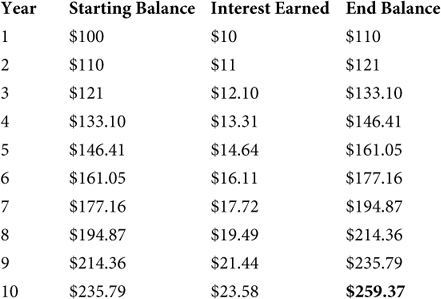

If you started with $100 and earned 10% interest a year, your account would look like this over the course of 10 years. Pay close attention to the earned interest column.

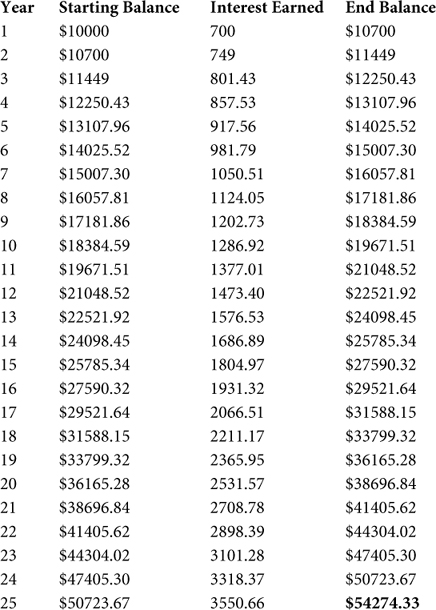

As you can see - in the first year, you only made $10 in interest, but by the 5th year, you were making nearly 50% more per year than you were in the first year. This is because you began earning interest on your interest. Now, I understand this chart is pretty underwhelming, but let’s apply this same concept to a $10,000 initial investment earning only 7% per year. However, let’s push this out to 25 years instead of only 10 years to really show the impacts of compounding.

The chart is for illustration purposes only. The two most important numbers to look at is your starting balance, year 1, and your ending balance year 25. As you can see, a single $10,000 turns into over $50,000 by year 25. If you add only another 10 years, that amount would be over $100,000 from a single $10,000 investment. Amazing, right? If that doesn’t excite you, let’s look at how many hours you replaced 25 years down the road from a single $10,000 investment. We will have to ignore taxes, as everyone’s situation is a little different but most people could invest this month 100% tax free and make these dollars stretch even further.

Imagine you make $20 p/h. In the first year alone you made the equivalent of 35 hours of work. Year 2 you have made the equivalent of 37 hours of work. Fast forward to year 10, you have made 64 hours of work. Finally, at year 25 you have made the equivalent of 177 hours of work. The total amount of hours ‘made’ during the entire 25 years is 2213 - that is over a year’s worth of work from a single $10,000. Imagine if you were saving $5,000 every year? Imagine how many hours you could have then. I won’t display the math but it would be more than 19,000 hours.

I hope this excites you, because it certainly excites me! I hope to encourage you to begin thinking about how investing can help you earn more than you make at your job to eventually be able to retire without worry. Now that is a much larger topic for an entirely different book. So, we will continue.

The idea that you can make money without putting in any effort is absolutely amazing!

But you must understand that this can also work against you. Imagine if you have a credit card at 19% interest. You owe $1000. You are paying $190 per year simply on interest. Now imagine you don’t pay for another year. Well, you would owe $1190 (and probably more because of late payment fees). How much interest would you pay based on this balance? $226.10. It is more than you would pay in the first year. Now - most people argue that negative interest doesn’t actually compound because you are making minimum payments, but that leads me to my next topic.

Minimum payments - death by a thousand cuts

If all you are paying is the minimum payment, your interest rate may as well be 1000% per year.

I don’t mean this literally, of course, as there would be a massive difference, especially in payments. However, people are obsessed with interest rates and the size of their payments, but not how much in dollars they are actually spending in interest. Put differently, people care very little about the overall cost of an item. Instead, they only care about the payment size. This is an interesting topic; one we will cover more in Chapter 7. However, I do believe that if all you are paying is the minimum, interest-only, payment you are really not getting ahead at all.

I see people all the time with debt loads exceeding $50,000 and they say that they are managing their payments and are not struggling. They are sometimes paying in excess of $1000 p/m just to service the debt, let alone pay the debt down. I certainly understand the struggle, as I have lived it. Looking back, I find it crazy that I thought that was OK. You may still think this is OK, but imagine someone making a modest household income of $80,000, split equally between both spouses. Let’s assume a 20% average tax rate, they would lose $16,000 to taxes. This leaves them with a net income of $64,000. Imagine if they were paying only $800 p/m in minimum interest payments. They would be paying $9,600 in interest a year, before principle is paid down. This also equates to 15% of their take-home income. That is outrageous!

If they were instead able to invest $800 p/m and earned 7% per year of compounding interest, they could have over $600,000 in a 25 year period. If they kept the debt, they would have paid $240,000 in interest, not including the principle that they were required to pay back.

Now, I understand that the idea is they would eventually pay off this debt. But remember, time is the key to compounding interest. As you saw in the previous tables, the longer you let your money work for you the harder it works and the more you make. So stop living in the ‘now’, with debt, and start living in the ‘now’ with a plan to get rid of the debt.

Once the debt is paid, you can use the money towards things you want or plan for the future with a plan to save for retirement. Both options are OK in my book. It surprises many people, but I don’t care how you want to live your life. All that I care about is that you are able to live your life in the way you want to truly live it. And for most people, that is without debt and stress.

Time-value of money

This one has math behind it, but is really a way to analyze your expenses to determine if they are really worth it for you. The easiest way that I have found, to determine whether a client really wants something, is to break it down by how much it costs them to have whatever they want on an hourly basis. For example, if you go see a movie and it costs you $15, for the ticket, and $20 for food and the movie is two hours long, the activity costs you $17.50 p/h.

You can start to truly understand the value you are receiving for an item based on how much you are spending on it on an hourly basis. For example - many people think cable is an expensive form of entertainment. For most, I would certainly agree but let’s assume that someone spends 2 hours watching prime-time cable a day, or approximately 60 hours of watched TV per month. For a standard cable package you might be paying approximately $100 per month. If you take your $100 and divide that by the numbers of hours watched per month you will find that you are only paying approximately $1.67 for every hour of TV watched. Compare that to the movie above and you are getting an absolute steal of a deal.

This calculation is simple. Simply take the total cost of an activity and divide it by however many hours of enjoyment you get out of it. One important step to remember is to not mix up time frames. For example do not divide an annual cost by the amount of hours you benefit in a month.

Opportunity Cost

Opportunity cost is an economics concept. To explain it in plain language, opportunity cost is the potential benefit you are not getting by doing another action. For example, if you only had 5 dollars and you could only buy either 2 apples or 3 oranges the opportunity cost of buying the apples is that you cannot buy the oranges and the opportunity cost of buying the oranges you cannot buy the apples.

To put this financially, if you finance a car and it costs you $500 per month, your opportunity cost would be what else you could do with that money. For example you could invest it and earn interest on your interest rather than paying the payment on the debt.

Make sense?

There is an opportunity cost in every aspect of your life, financial or not. Understanding what your potential opportunity costs are is crucial when you want to make decisions. What I urge you to try and do is think about how you are spending your money and where you could be spending your money instead and the potential benefit you could be receiving. This is your opportunity cost. Now ask yourself, what would you prefer? What you are doing now or what you could do with the funds instead?

To potentially sound like a broken record - there is no right or wrong answer. The point I would like to drive home is that you need to decide you want as opposed to comparing yourself against others.

These concepts are extremely important in assisting you to make great financial decisions, whether it be to help you choose an activity to do, help nudge you to save an extra $5 per month because you now understand the value of time and money when it comes to compounding interest, or by helping you think about the choices you make when it comes to how you spend your money.

My hope is the next time you have money to spend you take 30 seconds and consider these three concepts and how they apply to your decision.